The treatment of the Yeatses and the Mansions does not come at the beginning of this section, since some background is useful before looking at their possible interest in this area of astrology. The page is arranged as follows:

- 1. an overview of the rationale for the Mansions of the Moon, in the Introduction;

- 2. an outline of the Arabian system of the Mansions, both

- as a practical astrological system, drawing on the Indian and Hellenistic traditions of astrology, and giving Abenragel’s List of the Mansions

- and as a mystical system for arranging spiritual knowledge, using Ibn ‘Arabi’s List of the Mansions.

- 3. What we know about the Yeatses’ approach to the matter of the Mansions and what might have been available to them, including George Yeats’s List of the Mansions, and further general observations on the confusing situation they faced.

- 4. A look at the symbolic and talismanic images associated with the Mansions, along with H. C. Agrippa’s List of the Mansions.

| Introduction |

|---|

|

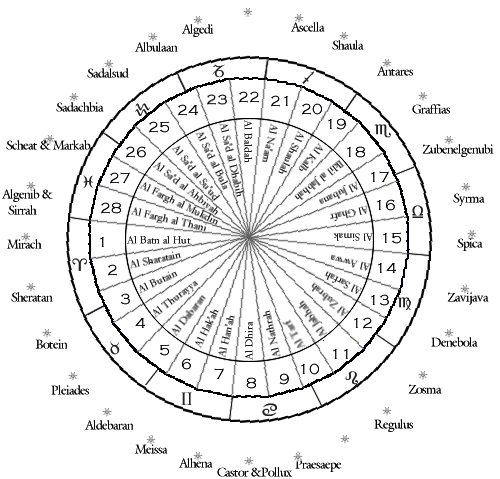

| The Arabic Mansions of the Moon, and one version of their alignment with the Zodiac. The fixed stars outside the circles are the traditional marker stars associated with each Mansion, and they often share a name, although the star names have been altered through European adoption (two Mansions do not contain any prominent stars). Because of the linkage with the fixed stars, which change their positions with respect to the Sun’s equinoxes with precession, there has been a greater tendency to treat the Mansions as sidereal than tropical, or to shift the Mansion which is regarded as the first one in accordance with the shift of the Vernal Equinox (see below). |

| The alignment given here is based on a list made by George Yeats, but using the Arabic names from Vivian Robson, The Fixed Stars and Constellations in Astrology (YL 1772). This takes the first Mansion as Al Batn al Hut (the Belly of the Fish), but in mediaeval times Al Sharatain (the Two Signs) was usually taken as the first, and anciently the first was Al Thurayya (the Many Little Ones, the Pleiades); see the Shifting Mansions below. |

Like the Sun, the Moon appears to go around the circle of the Zodiac, though its circuit lasts a month (of 27.32 days) rather than a year (see astronomy). The twenty-eight Mansions of the Moon divide the Zodiac in the same way as the twelve Signs of the Zodiac, marking out sectors of the circle of the sky, though, since the number of degrees in a circle, 360°, is not neatly divisible by 28, their span is an awkward 12°51'25.7" (a 364 degree circle would be neater). It is thought that the lunar system of division may predate the solar Zodiac at least as rough sectors, since the stars remain largely visible, and the Moon’s apparent motion against the background is clearly noticeable from night to night. The Encyclopaedia Britannica which Yeats had (1911 edition, YL 629) notes that the lunation cycle (the Moon’s synodic cycle, from the Greek synodos, meeting, conjunction) is the reason for dividing the Sun’s annual cycle into twelve, while the lunar Mansions derive from the Moon’s own motion:

| The synodical revolution of the moon laid down the lines of the solar, its sidereal revolution those of the lunar zodiac. The first was a circlet of "full moons"; the second marked the diurnal stages of the lunar progress round the sky, from and back again to any star. The moon was the earliest "measurer" both of time and space; but its services can scarcely have been rendered available until stellar "milestones" were established at suitable points along its path. Such were the Hindu nakshatras, a word originally signifying stars in general, but appropriated to designate certain small stellar groups marking the divisions of the lunar track. |

| "Zodiac", The Encyclopaedia Brittanica, Vol. 28, 995. |

Since the Moon’s sidereal revolution is 27.32 days, the number of Mansions has been approximated as both 27 and 28: in the most commonly used Indian system, there are 27 nakshatras, while 28 divisions are used in the Arabic and Chinese systems, as well as an older Indian system. (For a comparative table of the stars involved in lunar Mansion systems from Babylon, Arabia, India and China, drawn up by David B. Kelley, click here, and for a consideration of the origins of the Mansions, in India and China, see Philip Yampolsky, "The Origin of the Twenty-eight Lunar Mansions", Osiris IX [Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger B.V., 1950; 1984] 62-83.)

The Arabic Mansions of the Moon

The term ‘Mansion of the Moon’ or ‘Station of the Moon’ is the usual translation into English, via the Latin (mansio, dwelling, and statio, position or abode), of the Arabic term manzil al-qamar (plural manâzil; station, resting-place of the Moon, more after the manner of a camel train than an actual dwelling, certainly not a grand one). The Arabs are thought to have taken a local pre-Islamic weather-predicting system of anwa’, based on the star groups which rose just ahead of the Sun at a given time of the year, and to have combined it with the Mansion system of the nakshatras from Indian astrology. On the origins of the Arab system, see Giuseppe Bezza, "Du Calendrier naturel à l'Astrologie. Quelques observations sur la prévision du temps dans la littérature arabe du Moyen Age", Actes du V Séminaire Maroco-Italien (Cosenza: Unesco, 1999).

In A Vision A, Yeats notes that the number of his Phases ‘is that of the Arabic Mansions of the Moon but they are used merely as a method of classification and for simplicity of classification their symbols are composed in an entirely arbitrary way’ (AV A 12). Despite this dismissal, and despite the fact that Yeats is dealing with phases rather than the path of the Moon, there are lingering elements that seem to go beyond just classification. In another piece of ‘classification not symbolism’ (AV B 196), Yeats fits his Phases of the Moon to the months of the year and therefore to the solar Zodiac, on the basis that all cycles are linked in some way to each other (see Making Twenty-Eight Twelve). Although the phases of the Moon, which follow the synodic cycle of 29.53 days and cover more than 360°, are separate from and independent of the Moon’s sidereal position (for more, see the Lunar Cycle), the two are inevitably linked in the mind of the observer, so that there is a strong impulse to bring the cycle of the phases together with the Mansions of the Moon, particularly on the part of artists and those who do not need to be too accurate or practical in their reckoning. Indeed, within artistic and symbolic representations, as opposed to astronomical and astrological, the various cycles are almost always superimposed on each other.

|

Miniature from Zubdat al-Tawarikh (ca. 1580), an Ottoman survey of world history by Seyyid Loqman Ashuri. It shows, from the centre: the ancient planets (the Moon with a mirror; Mercury as a scribe; Venus with a dulcimer; a haloed Sun; Mars as a warrior; Jupiter as a worthy; Saturn as an ascetic), the signs of the Zodiac in a clockwise order, the Moon's phases in an anti-clockwise order aligned with the Mansions of the Moon. |

The twenty-eight letters of the Arabic alphabet and the symbolic significance of the Moon in Islam, particularly the crescent Moon, give the Mansions a particular significance in Arabic astrology. It is through the Arabs that Hellenistic astrology, including that of the Hermetic Corpus, and Indian astrology, along with the positional number system, were transmitted to the Europeans during the Middle Ages. During the great efflorescence of Islamic translation and science, roughly from the ninth to the thirteenth centuries CE, there were many writers in Arabic on astrology, and almost all include some treatment of the lunar Mansions, usually derived ultimately from the Hellenistic system of Dorotheos of Sidon (Dorotheus Sidonius; first century CE) influenced by the Indian nakshatras. Much of the material, but by no means all, was translated into Latin during the European Middle Ages, usually in Spain, where Islam and Christendom met, along with Judaism. The most frequently cited authors include: Mâshâ’allâh ibn Atari (Messahalla; fl. 800 CE), Abû ‘Ali al-Khayyat (Albohali; 770-835 CE), Abû Ma‘shar (Albumasar; ca. 786-885 CE), Al-Qalandar (Archandam, Alchandreus; identity uncertain), Al-Kindî (Alkindus; 795-865 CE), Al-Farghânî (Alfraganus; fl. 840 CE), Al-Qabisi (Alcabitius; d. 967 CE), ‘Alî ibn abi ’r-Rijâl (Haly Abenragel, fl. 1020 CE), Al-Birûnî (Alberuni; 973-1048 CE).

Also probably from Spain, and certainly in its present form, is an Arabic text called Ghâyat al-Hakîm, ‘The Goal of the Wise’, known in Europe by the name of its declared author as Picatrix, a grimoire with a powerful reputation and disordered structure. A useful summary of the contents of the Picatrix and of translations into various languages appears at the Esoteric Archives’ site.

The table below summarises the lists of the Mansions of the Moon given in a Latin translation of ‘Alî ibn abi ’r-Rijâl, Albohazen Haly Filii Abenragel libri de iudiciis astrorum, summa cura ... latinitati donati, per Antonium Stupam, published in printed form by Henricus Petrus in Basel in 1551 (pp. 342-46; an earlier version was published in Venice in 1503). The topics are rearranged slightly and kept in semi-note form for brevity. The focus is almost entirely on ‘catarchic’ astrology, that is the selection of propitious times to begin things and, with respect to what is favoured by the Moon’s position in the various Mansions, Abenragel’s list is a summary of Indian and Hellenistic traditions rather than an exposition of Arabian astrology or any ideas of his own. The enterprises involved vary from the important to the trivial, from marriage to when to put on new clothes, and Dorotheos also comments on the outcome of processes started involuntarily under a particular Mansion, such as captivity. Certain enterprises are favoured and others particularly cautioned against depending on the Moon’s position, though, for good fortune in the ventures favoured by a Mansion, the Moon must also be free from bad aspects from other planets (see Astrology). Some elements seem to be influenced by the Zodiac sign (interestingly Virgo seems to favour marriage with non-virgins), and characteristics often repeat for two or more consecutive Mansions. It is interesting that in European adoption the practice seems to have moved away somewhat from the deciding when to start a venture to focus more on magical operations and the making of talismans (see the Mansions’ Images), although the matters favoured may be similar. This seems more superstitious in some respects, but it also takes the burden off waiting for the appropriate time to do something, as long as the talisman has been made at the right time. The lists here are incidentally a fascinating side-light on the possible pre-occupations of their period, though probably more the time of the original sources, than of ‘Alî ibn abi ’r-Rijal himself, or of the Latin translators. Certain things like when to have a haircut and put on new clothes seem strangely unimportant, while Dorotheos’ terms of reference, in particular, are very much those of a male, slave-owning soldier, in danger of capture.

| The Mansions of the Moon according to Abenragel (ca. 1000 CE) Elections according to the Moon in the Mansions | Name given & Arabic name | starting degree | Indian opinion | Dorotheos |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ilnath Al Sharatain | 0° 0' 0" Aries | Good for taking medicines, pasturing livestock, making journey, except second hour | Good for buying tame animals, for journeys, especially voyages, for making arms, planting trees, cutting hair or nails, putting on new clothes. Bad for contracting marriage (holds for Moon in Aries), making partnerships, or buying slaves, who will be bad, disobedient or run away. If captured, prison will be bad and strong. |

| 2 | Albethain Al Butain | 12° 11' 26" Aries | Good for sowing and making journeys. | Bad for marriage, buying slaves, and for boats and prisoners similar to Alnath |

| 3 | Athoraie Al Thurayya | 25° 22' 52" Aries | Good for trading and revenge on enemies; indifferent for travel. | Good for buying tame animals and hunting, for all matters involving fire, and for doing good. Bad for marriage, and making partnerships, especially with those more powerful. Bad for buying cattle or flocks, for planting trees, sowing or putting on new clothes. If captured, prison will be strong and long. Water journeys will bring fear and danger. |

| 4 | Addauennam Al Dabaran | 8° 34' 18" Taurus | Good for sowing, for putting on new clothes, for receiving women and feminine things, for demolishing a building or starting a new one, for making a journey, except for third part of day. | Good to build a house, which will be solid, and building in general, to dig a ditch, to buy slaves, who will be loyal and honest, and to buy livestock. Also good to be with kings and lords, for receiving power or honours. Bad to contract marriage, since woman will prefer another, or to enter partnerships, especially with those more powerful. Voyages will involve big waves. If captured, the captivity will be long but, if captured for skills, will be released through goodwill. |

| 5 | Alhathaya Al Hak‘ah | 21° 45' 44" Taurus | Good for contracting marriage, for putting boys to study laws, scriptures or writing, for making medicines, for making a journey. | Good for buying slaves, who will be good and loyal, for building, for travel by water, for washing head, indeed general washing, and cutting hair. Bad for partnerships. If captured, imprisonment will be long, unless captured for skills, when he will escape. |

| 6 | Alhana/Atabuen Al Han‘ah | 4° 17' 10" Gemini | Good for kings to declare war,enrollment of armies and cavalry, for knights seeking better pay, for the successful siege of a city, for smiting enemies and evildoers. Bad for sowing, seeking a loan, or burial. | Good for partnerships and ventures, associates will agree and be honest and loyal, for hunting, for journeys by water, though delays. Bad for taking medicine and for treating wounds. New clothes put on will soon tear. If captured, release within three days or very long imprisonment. |

| 7 | Addirach Al Dhira | 17° 36' 36" Gemini | Good for ploughing and sowing, for putting on new clothes, for women’s jewellery, for cavalry. Bad for journeys, except in last third of night. | Good for partnerships, which will be good and useful, with loyal and agreeable associates, for washing head, cutting hair and new clothes, for buying slaves and livestock, for smiting or making peace with enemies, for voyages towards destination, but delays on return. Bad for buying land, and for giving up medicine. If captured, unless he escapes in three days, he will die in prison. Likewise, if he has escaped something he fears, he will encounter it again. |

| 8 | Aluayra Al Nathra | 0° 0' 0" Cancer | Good for taking medicine, for cutting new clothes, for women’s jewellery and putting it on. Rain will bring benefit not damage. Bad for travel, except for last third of night. | Good for voyages, swift on outward and return journeys. Marriages contracted will be harmonious for a while, then discordant. A slave bought will deceitful, accuse his master, and run away. A partnership started will involve fraud on either side. If captured, long imprisonment. |

| 9 | Attraaif Al Tarf | 12° 11' 26" Cancer | Bad for sowing, journeys, entrusting anything to anyone, or seeking to harm anyone. | Good for voyages, outward and return, for reinforcing doors and making locks, for making beds and putting up bed-curtains, for transplanting wheat. Bad for partnerships, which will involve fraud on either side. Bad for cutting hair, or new clothes. Putting on new clothes may lead to drowning in them. If captured, long imprisonment. |

| 10 | Algebhe Al Jabhah | 25° 22' 52" Cancer | Good for contracting marriage, for sugar and what is made with it. Bad for journeys and entrusting anything, for putting on new clothes or for women’s jewellery. | Good for buildings, which will last, and for partnerships, benefiting all parties. If captured, at the command of a leader or because of great deed, and long, hard imprisonment. |

| 11 | Azobrach Al Zubrah | 8° 34' 18" Leo | Good for sowing and planting, for besieging. Indifferent for trade and journeys. Bad for freeing captives. | Good for buildings and foundations, which will last, and for partnerships, from which associates will gain. Good for cutting hair. Bad for new clothes. If captured, at the command of a leader, and long imprisonment |

| 12 | Azarfa Al Sarfah | 21° 45' 44" Leo | Good for starting all building, for arranging lands, sowing and planting, for marriage, for putting on new clothes, for women’s jewellery, for making a journey in the first third of day. | Good for buying slaves and livestock, once the Moon is out of Leo, since the Lion is a great devourer. (If he eats a lot it leads to stomach pains, power, boldness and obstinacy.) What is lent will not be returned, or only with great effort and delay. Voyages will be long, hard and dangerous, but not fatal. |

| 13 | Aloce Al Awwa | 4° 17' 10" Virgo | Good to plough, sow, make a journey, marry, free captives. | Good to buy a slave, who will be good, loyal and honest, to start building, to give oneself to pleasures and jokes, to come before a king or famous man, to take medicines, to cut new clothes, to wash or cut hair. Not bad to marry a corrupted woman, and, if marrying a virgin, the marriage will last a while. A voyage undertaken will involve delay in return. If captured, he will be injured in prison, but captivity will end well. |

| 14 | Azimech Al Simak | 17° 36' 36" Virgo | Good for marrying a woman who is not a virgin, for medicines, sowing and planting. Bad for journeys or entrusting something to someone. | Good to start a voyage and a partnership, which will be profitable and harmonious, to buy a slave, who will be good, honest and respectful. Marriage with a virgin will not last long, and it is not bad to marry a corrupted woman. If captured, he will soon escape or be released. |

| 15 | Algarf Al Ghafr | 0° 0' 0" Libra | Good to dig wells and ditches, to cure illnesses to do with wind, but not others. Bad for journeys. | Good for moving house, for adapting or preparing a house, its owner and site. Good to seek to do a good deed, to buy and sell, but selling slaves not livestock, because Libra is a human sign. Bad for both land and sea journeys. Marriage will not last in harmony, or only for a while. Partnerships entered will lead to fraud and discord. Money lent will not be returned. Bad for cutting hair. |

| 16 | Azebone Al Jubana | 12° 11' 26" Libra | Bad for journeys, trade, medicines, sowing, women’s jewellery, for cutting or putting on new clothes. | A slave bought will be good, loyal and honest. Bad for marriage, which will only last in harmony for a while, for partnerships, which will lead to dishonesty and mutual suspicion. If captured, he will soon be out of prison, if God wills. |

| 17 | Alidil Iklil al Jabhah | 25° 22' 52" Libra | Good to buy flocks and livestock, to change their pasture, to put on new jewellery and besiege towns. | Good for starting building, which will be solid and durable, for settling a dispute between two people, to foster love, and love begun will be absolutely solid and last for ever. Good for all medicine. Voyages started will bring anxiety and sorrows, but he will survive. Partnerships started will bring discord, and he who marries, will find his wife impure. Bad for selling slaves or cutting hair. |

| 18 | Alcalb Al Kalb | 8° 34' 18" Scorpio | Good for building, for arranging lands and buying them, for receiving honours and power. If it begins to rain, it will be wholesome, useful and good. Eastwards journeys are favoured. | Building undertaken will be solid. Good for planting and taking medicines. If a man gets married and the Mars is with the Moon here, he will find her not to be a virgin. If he enters a ship he will come out again. Bad for selling slaves, new clothes, cutting hair. Partnerships will result in discord. |

| 19 | Yenla Al Shaula | 21° 45' 44" Scorpio | Good for besieging towns and encampments, for disputing against enemies, for making a journey, for sowing and for planting trees. Bad for entrusting something to somebody. | If a man gets married, he will find her not to be a virgin. Bad for voyages, which will end in shipwreck, for partnerships, which will be discordant, for selling slaves, and very bad for a captive. |

| 20 | Alimain Al Na’am | 4° 17' 10" Sagittarius | Good for buying animals. Rain will be good and do no harm. Indifferent for journeys. | Good for buying small animals. Bad for partnerships and captivity. |

| 21 | Albeda Al Baldah | 17° 36' 36" Sagittarius | Good for starting any building, for sowing, for buying lands or livestock, for buying and making women’s jewellery and clothes. Indifferent for journeys. | A woman who is divorced or widowed will not marry again. Indifferent for slaves bought, since they will think much of themselves and will not humble themselves to their masters. |

| 22 | Sahaddadebe Al Sa’d al Dhabih | 0° 0' 0" Capricorn | Good for medicine and journeys, except for last third of day. Good for putting on new clothes. | Good for entering a partnership, which will bring profit and usefulness, and for entering a ship, though there will be great anxieties from a strong desire to return and the like. A man who becomes engaged will break the engagement before the wedding and die within six months, or the couple will be in conflict and live badly, with the wife mistreating the husband. Bad for buying slaves, who will do ill to their master, or run away, or be irksome or bad. If captured, he will soon gain freedom. |

| 23 | Zadebolal Al Sa’d al Bula | 12° 11' 26" Capricorn | Good for medicine, for putting on new jewellery and clothes, for a journey in the middle third of day. Bad to entrust something to someone. | Good for partnerships. Bad for marriage, since wife will mistreat husband and they will not be together much, for entering a ship, if a short voyage is wanted, for buying slaves. If captured, he will soon regain liberty. |

| 24 | Zaadescod Al Sa’d al Su’ud | 25° 22' 52" Capricorn | Good for medicine, sending out armies and soldiers. Indifferent for journeys. Bad for merchandise, jewellery, putting on new clothes, marrying. | A slave bought will be strong, loyal and good. Bad for partnerships, which will end in great harm and conflict, and for entering a ship. Marriage will only last a while. If captured, he will soon be free. |

| 25 | Sadalabbia Al Sa’d al Ahbiyah | 8° 34' 18" Aquarius | Good for besieging towns and encampments, for going into a quarrel, for pursuing enemies and doing them harm, for sending messengers. Favours journeys southwards. Bad for marriage, for sowing, for merchandise, for buying livestock. | Good for buying slaves, who will be strong, loyal and good, for building, which will be solid and durable, and for voyages, though there will be delays. Marriage will only last for a while. Bad for partnerships, which will end badly and harmfully, and a slave will escape. |

| 26 | Fargalmocaden Al Fargh al Mukdim | 21° 45' 44" Aquarius | Good for making a journey in the first third of the day, but the rest is good for neither journeys nor any other beginning. | Good for building, which will be solid and durable, for buying a slave, who will be loyal and good, for entering a ship, though there will be delays. Bad for partnerships. Marriage will not last. If captured, he will be in prison for a long time. |

| 27 | Alfargamahar Al Fargh al Thani | 4° 17' 10" Pisces | Good for sowing, and useful for trading. Good for marriage. Indifferent for journeys, except for middle third of night when very bad. Bad for entrusting something to someone, or lending anything. | If starting a partnership, it will begin well but end in harm and conflict. Entering a ship will bring damage, dangers and travails. A slave bought will be bad. If captured, he will not leave prison. |

| 28 | Bathnealoth Al Batn al Hut | 17° 36' 36" Pisces | Good for trade, sowing and medicines. Good for marriage. Indifferent for journeys, except for middle third of night when bad. Bad for entrusting something to someone, or lending anything. | A partnership started will begin well but end badly. A slave bought will be bad, irascible and very proud. If captured, he will not leave prison. |

Johannes Hispalensis translated a good number of Arabian sources on astrology, and gives his own summary of all these works in Epitome Totius Astrologiae (written ca. 1142); he also gives the Indians and Dorotheos as his authorities for the Mansions, and the meanings are largely in accordance with Abenragel’s reports. We know that the Yeatses were referred to this book (see The Yeatses and the Mansions for this and further consideration of mediaeval Latin sources).

Mystical Astrology

A very different approach is seen in an influential system of correspondences constructed by the Sufi Master, Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabi, who was born in Murcia, in the Arab Spain of Al-Andalus, in 1165 and died in Damascus in 1240 CE (a life-span that pre-dates Yeats’s [1865-1939] by 700 years almost exactly). Ibn ‘Arabi’s exposition is one of mystical symbolism rather than practical astrology, using the Mansions to organise a chain of being from the uncreated first cause through levels of celestial manifestation and the elemental world to man and the process of hierarchy itself. The cosmos expounded gives a theoretical explanation of the tropical system of the Zodiac, placing the Towers of the Zodiac in the Sphere of the Starless Sky, above that of the Sphere of the Fixed Stars, and below the Sphere of the Divine Pedestal and the Sphere of the Divine Throne. Effectively he, therefore, gives the equinoxes precedence over the precession of the stars, and ties the First Point of Aries to the Vernal Equinox, which is seen as closer to the first movers than the ‘fixed’ stars.

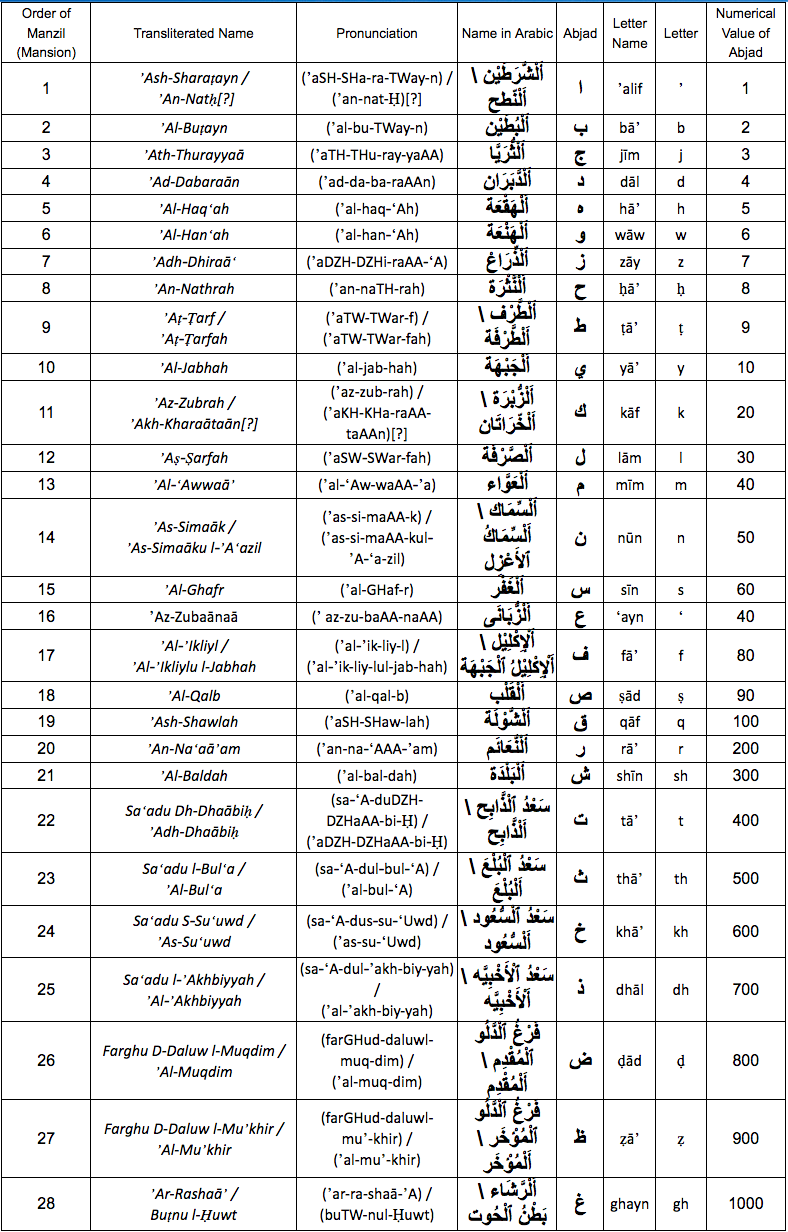

According to Titus Burckhardt’s summary of Ibn ‘Arabi’s ideas, drawn from a variety of his works in Mystical Astrology According to Ibn ‘Arabi, the true start of the Mansions appears to correspond with the Moon’s Ascending Node (see the Draconic Cycle), but for symbolic purposes it is aligned with the Vernal Equinox. Ibn ‘Arabi gives a series of correspondences with Divine Names or Attributes, as well as the hierarchy of creation and the alphabet and, with respect to the alphabet, asserts that ‘It is not like people think, that the Mansions of the Moon represent the models of the letters; it is the 28 sounds which determine the lunar mansions’ (Burckhardt, 35). (See the Ibn ‘Arabi Society’s site for more detail, and Burckhardt.) The sequence given here appears in The Revelation of Mecca, but the names of the Mansions are not given, so I have taken them from Vivian Robson, The Fixed Stars and Constellations in Astrology, which follows a looser convention of transcription.

| The Mansions of the Moon according to Ibn ‘Arabi (ca. 1200) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [name] | meaning | from | attribution | letter | Divine Attribute | |

| 1 | Al Sharatain | The Two Signs | 0° Aries | The First Intellect, the Pen | Hamza & Alef | Divine Essence |

| 2 | Al Butain | The Belly of Aries | 12°51'22" Aries | The Universal Soul, the Preserved Tablet | Hâ’ (unstressed h) | The One Who Calls Forth |

| 3 | Al Thurayya | The Many Little Ones | 25°42'51" Aries | Universal Nature | ‘Ayn | The Interior |

| 4 | Al Dabaran | The Follower | 8°34'17" Taurus | Universal Substance, prima materia | Hâ (stressed h) | The Last |

| 5 | Al Hak‘ah | The White Spot | 21°25'40" Taurus | Universal Body | Ghayn (gh) | The Manifest |

| 6 | Al Han‘ah | The Mark | 4°17'09" Gemini | Form | Khâ (kh) | The Wise |

| 7 | Al Dhira | The forearm | 17°08'34" Gemini | The Throne | Qâf (q) | The All-Encompassing |

| 8 | Al Nathra | The Gap or Crib | 0° Cancer | The Footstool | Kâf (k) | The Grateful |

| 9 | Al Tarf | The Glance | 12°51'22" Cancer | The Self-Existing Ultimate Sphere, the Starless Sky, the Zodiacal Towers | Jîm (j) | The Independent, the Rich |

| 10 | Al Jabhah | The Forehead | 25°42'51" Cancer | The Sky of the Fixed Stars, the Sphere of the Stations, the Sun of Paradise, the Roof of Hell | Shîn (sh) | The Powerful |

| 11 | Al Zubrah | The Mane | 8°34'17" Leo | The First Heaven, the Sphere of Saturn, the Sky of the Visited House and Lotus of the Extreme Limit, the Abode of Ibrahim (Abraham) | Yâ (y/î) | The Lord |

| 12 | Al Sarfah | The Changer | 21°25'40" Leo | The Second Heaven, the Sphere of Jupiter, the Abode of Musa (Moses) | Dâd (stressed d) | The Knowing |

| 13 | Al Awwa | The Barker | 4°17'09" Virgo | The Third Heaven, the Sphere of Mars, the Abode of Harun (Aaron) | Lâm (l) | The Victorious |

| 14 | Al Simak | The Unarmed | 17°08'34" Virgo | The Fourth Heaven, the Sphere of the Sun, the Abode of Idris (Enoch, Hermes) | Nûn (n) | The Light |

| 15 | Al Ghafr | The Cover | 0° Libra | The Fifth Heaven, the Sphere of Venus, the Abode of Yusuf (Joseph) | Râ (r) | The Form-Giver |

| 16 | Al Jubana | The Claws | 12°51'22" Libra | The Sixth Heaven, the Sphere of Mercury, the Abode of ‘Isa (Jesus) | Tâ (stressed t) | The Numberer |

| 17 | Iklil al Jabhah | The Crown of the Forehead | 25°42'51" Libra | The Seventh Heaven, the Sphere of the Moon, the Abode of Adam | Dâl (d) | The Evident |

| 18 | Al Kalb | The Heart | 8°34'17" Scorpio | The Sphere of Ether, Meteors and Fire | Tâ (unstressed t) | The Seizer |

| 19 | Al Shaula | The Sting | 21°25'40" Scorpio | Air | Zây (z) | The Living One |

| 20 | Al Na’am | The Ostriches | 4°17'09" Sagittarius | Water | Sîn (s) | The Life-Giver |

| 21 | Al Baldah | The City | 17°08'34" Sagittarius | Earth | Sâd (stressed s) | The Death-Giver |

| 22 | Al Sa’d al Dhabih | The Fortune of the Slayers | 0° Capricorn | Minerals and Metals | Zâ (stressed z) | The Precious |

| 23 | Al Sa’d al Bula | The Fortune of the Swallower | 12°51'22" Capricorn | Plants | Thâ (th) | The Nourisher |

| 24 | Al Sa’d al Su’ud | The Fortune of the Fortunate | 25°42'51" Capricorn | Animals | Dhâl (dh) | The Humbler |

| 25 | Al Sa’d al Ahbiyah | The Fortune of the Hidden | 8°34'17" Aquarius | The Angels | Fâ (f) | The Strong |

| 26 | Al Fargh al Mukdim | The First Spout | 21°25'40" Aquarius | The Jinn | Bâ (b) | The Subtle |

| 27 | Al Fargh al Thani | The Second Spout | 4°17'09" Pisces | Humanity | Mîm (m) | The Uniter |

| 28 | Al Batn al Hut | The Belly of the Fish | 17°08'34" Pisces | The Hierarchy of the Degrees of Existence, not their manifestation | Wâw (w/û) | The One Who Elevates by Degrees |

(A list with the full Arabic is available here or at the end of the page.)

The movement away from Divine Essence in the First stage passes through stages of universal Archetypes and reaches the highest levels of celestial manifestation at stages Seven and Eight around the Summer Solstice, the spheres beyond the manifest cosmos. The planetary sequence starts with Saturn and the Sun is at the central point of this sequence, corresponding with the equinoctial point of Libra. Earth represents the most solid simple element, and is placed at the Winter Solstice, after which come the mixed forms, with a form of ascent.

Although it is unlikely that Yeats would have known about Ibn ‘Arabi’s schema, there are some interesting parallels in the hierarchy or cycle outlined, in particular with the placement of the Divine Essence with the First Mansion, and the Light with the opposite point.

All the same, Yeats was certainly interested enough in Arabian wisdom to concoct an elaborate story involving Michael Robartes and the Judwalis in the first version of A Vision, locating the adventures at various places in Arabia and Ottoman Palestine, as well as giving one of the supposed origins of the System to a Syriac Christian at the Caliph’s court in Baghdad, Kusta ben Luka, a translator from the ninth century CE.

The Yeatses and the Mansions

As the schema of the twenty-eight phases of the Moon first began to emerge in the Automatic Script at the end of November 1917 the Yeatses must have been intrigued by the possibility that they bore some relation to the twenty-eight Mansions of the Moon from Arabic astrology. Only three days after the first appearance of the ‘28 days of [Moon]’, the Automatic Script features the term ‘The 28 mansions’ (YVP 1 119) in one of George’s answers on 25 November 1917 and in a subsequent question on that day Yeats was wrestling with the problem that one solar day ‘which equals one mansion of moon would represent one incarnation & time after’, in other words the period between lives (YVP 1 120). On the 30 November George’s reply to the first numbered question contains another name for these divisions of the Zodiac, ‘the stations 28 of moon’, and Yeats’s next question was whether these days ‘correspond to the lunar mansions’ to which the answer was apparently ‘Yes’ (YVP 1 126).

| He [Aurelius] hym remembred that, upon a day,

At Orliens in studie a book he say Of magyk natureel, which his felawe, That was that tyme a bacheler of lawe, Al were he ther to lerne another craft, Hadde prively upon his desk ylaft; Which book spak muchel of the operaciouns Touchynge the eight and twenty mansiouns That longen to the moon—and swich folye As in oure dayes is nat worth a flye,— For hooly chirches feith in oure bileve Ne suffreth noon illusioun us to greve. | He remembered that, one day,

While studying in Orléans, he had seen a book About natural magic,* which his companion, Who was then a bachelor of law, Even though he was learning another skill, Had privately left on his desk. This book spoke much about the operations Concerning the twenty-eight mansions That belong to the moon—and such folly As nowadays is considered worthless— Since the holy church's faith does not Allow any illusion to harm our belief. | ||

‘The Franklin’s Tale’, The Canterbury Tales, Fragment V (Group F) 1123-1133 | *magic which harnesses the forces of nature, and does not involve invocation of spirits or demons. | ||

George Yeats also highlighted a passage from Skeat’s notes with double lines: after directing his reader to Ludwig Ideler’s Untersuchungen über den Ursprung und die Bedeutung der Sternnamen (1809) for the positions of the Mansions, Skeat comments that, since Ideler does not give their significance, ‘For the influence of the moon in these mansions, we must look elsewhere, viz. in lib.i. cap. 11, and lib. iv. Cap. 18 of the Epitome Astrologiae of Johannes Hispalensis’ (from The Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer [Oxford: Clarendon, 1894], Vol. 5, 392; see CVA notes 10). As has been mentioned, the Arabic Mansions had passed into mediaeval European usage through the work of the Spanish translators, especially those of Toledo, and, in his Epitome Totius Astrologiae ("The Summary of All Astrology"), Johannes or Joannes Hispalensis (John of Seville) brings together astrological teaching from a variety of sources, including Arab writers, many of whom he had also translated. At some stage the Yeatses must have followed up these references.

Published in printed form in 1548 but dated internally to 1142, the Epitome does not give the Arabic names of the Mansions, but it does give the Latin names, and quite a full treatment of their significance according to Dorotheus of Sidon. In the context of mundane astrology, Joannes Hispalensis also quantifies the ‘virtues’ (virtutes) of the Moon, by which he means its strength within the figure of a horoscope, according to its phase, giving the twelve somewhat unequal ‘portals’ or ‘doors’ (ianuae), but he does not assign any further characteristics to them. One other point that could have been of interest to the Yeatses is his method of predicting the year to come, through taking the horoscope of the Moon’s last conjunction or opposition prior to the Sun’s entry into Aries, the New Moon or Full Moon in March.

Another resource which the Yeatses could well have consulted would have been the works of Cornelius Agrippa, in particular his De Occulta Philosophia, of which they perhaps already owned a copy (YL 5) and which Yeats certainly knew in J. F.’s English version (1651). Agrippa asserts the importance of the Mansions in his second Book on Celestial Magic stating in Chapter 33, entitled ‘Concerning the 28 mansions of the Moon, and the powers of the same’, that:

| Since the Moon measures the whole Zodiac in the space of twenty-eight days, hence the wise men of the Indians and the most ancient Astrologers granted twenty-eight mansions to the Moon, which are situated in the eighth sphere and which, as Alpharus says, are allotted diverse properties and names from the diverse constellations and stars of the same which are contained in them; while the Moon travels through these it derives differing powers and differing virtues. . . . And in these twenty-eight mansions lie many secrets of the wisdom of the ancients, and through them are worked wonders in all things which are under the circle of the moon. . . . |

This chapter gives a list of the Mansions, in the normal, garbled mediaeval form of the Arabic names, the meaning in Latin, their positions and a brief summary of their significance, while a later chapter gives images for each of the Mansions to be used in the manufacture of talismans according to the magical intentions of the maker (see Agrippa’s list below). These images are of a similar nature to those which Yeats tried to develop for each of the Phases (see Phase Images), although they are usually very different in detail; however, both combine disparate and strange images, which are sometimes quite violent. For instance, a talisman for revenge and enmity should be made out of red wax when the Moon is in the fourth Mansion (Aldebram or Aldelamen, the eye of the bull), with the image of a soldier on horseback, holding a snake in his right hand, which should then fumigated in incense of red myrrh and storax, while one to aid childbirth and to cure the sick, should be made out of gold with a lion’s head on it when the Moon is in the tenth Mansion (Algeliache or Aglebh, the lion’s forehead), fumigated with ambergris. The only image which coincides in Yeats’s and Agrippa’s lists is that of a Janus figure which represents both Yeats’s Phase 18 and Agrippa’s Mansion 21, Abeda (see the list below).

Giordano Bruno’s lists of astrological images, including those of the Mansions, are very similar to Agrippa’s. These figures are given not in the context of talismans or magic, since, ostensibly they are part of his mnemonic system; however, in the words of Frances Yates, the “two books on the art of memory” which he published while resident in Paris “reveal him as a magician”. Much of his more explicit magical writing was in fact not published until long after his death, with De Magia only appearing in 1891. The images which appear in De umbris idearum (1582) are not exactly the same, but, although there are other sources which he could have used, Agrippa is the most likely, particularly given other echoes elsewhere in his works. Bruno, however, develops and embellishes to a greater or lesser extent from what any sources could offer him. With reference to the examples given above, Bruno gives for the fourth Mansion a soldier on horseback with a snake in his right hand and dragging a black dog with his left, for the tenth a woman in childbirth, in front of whom there is a golden lion and a man in the attitude of a convalescent, and for the twenty-first, two men back to back, each picking up shaved hairs.

Agrippa’s lists of the Mansions of the Moon and their images appear to be derived in turn from the Picatrix, possibly the best-known magical text dealing with the Mansions. Although it was only available in manuscript form at the time when Yeats was working, there are copies in Oxford, London and Paris; MacGregor Mathers who ‘had copied many manuscripts on ceremonial magic and doctrine in the British Museum, and was to copy many more in Continental libraries’ (Au 183) would almost certainly have known it. The Picatrix not only uses the positional Mansions of the Moon (see table above) but also deals with the relational phases of the Moon, although only to the extent of characterising the four quarters, along with the New Moon; however both are treated in the context of magical ritual, and do not have anything to do with people’s characters.

Even if Yeats decided not to research the Mansions himself, Frank Pearce Sturm offered him plenty of information concerning them, and in a series of letters in 1924 (Frank Pearce Sturm, 83-87), considering the role of Yeats’s Kusta ben Luka, he mentioned Arabian philosophers and astrologers, referring to Alkindi, Albumazar, Thebit ben Corat and Rhazes, as well as a manuscript in the Bodleian "entitled The Book of the 28 Images of the Moon and the 28 Mansions and the 54 Angels Who Serve the Images". He noted that in "the Middle Ages, when Arabian learning was lost, the Images of the Moon became the 28 Judges of Geomantic Divination". Sturm also claimed very particular knowledge:

| I know a deal about this that is in no book, for it comes from the memory of one long dead. For twenty-five years some mind that is not my own has tried to force me to write a certain system of philosophy, but I am not yet convinced that it is worth writing. I used to think that the spirit of a monk, burnt for heresy early in the 12th century was my informant, but I would rather believe him to have been myself in a past life, as I once saw him in a crystal vision, with a tonsured head sticking out of a cowl, in a big gloomy lecture hall. He died with his book in his mind, & now troubles me with his uncompleted task. When I am in that mood I take up a pen and make up sentences out of his book. I have a whole collection of them, and if I don’t call the automatic writing it is not because I don’t believe they are. |

| (Frank Pearce Sturm, 85) |

Although Sturm was indicating a willingness to delve into Arabian and Mediaeval lunar astrology, as well as his own unquiet spirit’s ideas, Yeats seems to have taken little interest.

There are other possible places in which the Yeatses could have found lists of the Mansions, though without any tangible evidence that they did: either Western compilations of Arabic source material, similar to the Epitome, such as Guido Bonatti’s Liber introductorius ad iudicia stellarum, or actual translations of original Arabic works, some, such as that of Abenragel cited above, available in printed form, and others, such as the pseudo-Hermes, only in manuscript. All these writers, though, give very similar lists, most in fact derived ultimately from Dorotheos of Sidon and Indian sources.

There is, however, one final source that they did use, which is significantly different from the others. It is a list of Mansions of the Moon in George Yeats’s hand, and was filed with the Automatic Script from 27 June 1918; it is published in George Mills Harper’s The Making of Yeats’s "A Vision" (Appendix C; Vol. 2, 419). As the heading ‘560. Athanasius Kircher’ indicates, the list was derived from a work of the Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher, in fact Lingua Aegyptiaca Restituta (Rome, 1643). Kircher was among the first Europeans to study the Coptic language, surmising that Coptic was the descendent of the language of Ancient Egypt, although Coptic had already almost died out as a spoken language by his day and become restricted to the liturgy of the Coptic Church. Kircher had access to a bilingual Arabic-Coptic word list, which had been prepared in the fourteenth century by Barakat ibn Kabar (d. 1324), the priest of the Hanging Church in Cairo. This work was called The Great Ladder (Scala Magna in Kircher’s Latin or al-Sullam al-Kabêr in Arabic) and Kircher added a Latin translation, making it a trilingual lexicon. He published it under the title Lingua Aegyptiaca Restituta, ‘The Egyptian Language Restored’, since he was among the first to surmise that Coptic descended from the language of Pharaonic Egypt.

As a supplement to the word lists, he examined areas by topic, among them ‘The Egyptian names for the stars’ where he sought to piece together the astronomy/astrology of Ancient Egypt. A good part of this chapter is centred on the Mansions of the Moon and was repeated, with a few embellishments, in his magnum opus on Egypt, Oedipus Aegyptiacus (Rome, 1652-54). The two lists both have inaccuracies in the starting and finishing degrees of the Mansions, but they are distinct, and the anomalies in George Yeats’s list indicate that her source was Lingua Aegyptiaca Restituta, where the list starts on page 560.

For a clearer, larger image, click here.

For a slightly more detailed version of Kircher's list without George Yeats's notes click here

I have amended the list slightly from Harper’s reading in the case of Mansion 4, ‘also the Hour of the [indecipherable word] with her sons’, since it is clearly a translation of ‘gallina caeli’. The use of a capital ‘H’ indicates that George Yeats probably read ‘Hori’ correctly as ‘of Horus’, although the capitalisation is generally not reliable. I have written a full article (‘George Yeats and Athanasius Kircher’, online PDF version) about George Yeats’s list and the links with Athanasius Kircher in the Yeats Annual 16, 2005. Unfortunately in the transmission to printing, the special characters lost their formatting and the online version above is more correct.

George understood Latin, but appears to have been slightly cavalier with the dictionary, taking cubitus as bed rather than the cubit measure or forearm and reading frons as frons, frondis, a frond, bough or leafy branch, rather than frons, frontis, forehead, front or brow. In both places the context makes the alternatives clear, so it indicates that she may have been rushing to some degree. She would have been able to read the Coptic as well, since the Golden Dawn required its members to know the names of Egyptian deities in their Coptic forms (Kircher’s assumption about Coptic had been proved right, and Coptic Egyptian is more or less the ancient Egyptian language in the Greek alphabet, giving it vowels and making it more readily accessible). George would probably have recognised most of the Hebrew as well, since the language and alephbet were fundamental from studies in Cabbala in the Golden Dawn. That was still not enough, though, and the gaps in George Yeats’s list are understandable when one sees the pages are also scattered with Greek, Arabic, Estranghelo and Amharic scripts.

Though Kircher was correct about the Coptic language’s relationship with Egyptian, most of his other assumptions were wrong, even if they were based on the best classical authorities. These included the assumption that the hieroglyphs were an entirely symbolic or ideogrammatic writing with no phonetic component, and that the Greek language and alphabet were derived from the Egyptian. It may seem obvious now that the alphabet is an adaptation of Greek, but Kircher saw the letters formed from the ibis, ram, bull and so on, and then taken to Greece. To us the similarities between Greek words and Coptic ones (such as ‘polis’ for city-state, ‘karthian’ for heart, or ‘stephani’ for crown) show Egyptian borrowing during the Hellenistic period, but to Kircher it seemed that the influence had gone the other way. The coincidence between the Arabic names for the Mansions and the Coptic ones is also clear and the names seem to be often Greek translations of the Arabic names, especially in the second half of the list, and so it seems probable that the list is largely a version of the Arabic lunar system, especially since the essential Egyptian system is strongly solar and decimal, using the 36 decanates of the Zodiac (ten days of the Sun’s movement) rather than the 28 Mansions (one day of the Moon’s movement).

|

[This will be extended further.] |

|

The Shifting Mansions

The Mansions’ names often tie them to a constellation or sign of the Zodiac, for example, the ram's belly, the lion's mane, the scorpion's sting. It is also clear that with the dislocation of the constellations from their associated signs of the Zodiac, owing to the natural phenomenon of the precession of the equinoxes, if the Mansions remain tied to the stars rather than the signs, then some of the anomalies that are gradually established between the two series start to make the system look slightly absurd, thus Al Batn al Hut, "the belly of the fish", from the constellation of Pisces will now be found in the tropical sign of Aries. This is because the system of the Mansions is strongly linked to the stellar patterns in the night sky rather than to the Sun’s equinoxes and solstices (its tropoi, turning points), which form the basis for Arabian and European astrology, and the Mansions therefore creep 'forwards' as the precession of the equinoxes shifts the tropical Zodiac backwards against the background of the stars.

The exact amount of the drift varies with the date. The texts usually derive from Arabic writers of the tenth and eleventh centuries, whose works were transmitted into Europe through mediaeval translations circulated in manuscript, which, in turn, were then sometimes printed some centuries after that, with no updating. There is, therefore, room for a great deal of uncertainty, since each year adds a further slippage of 50.4", and therefore 1º every 71½ years. Such shifts can be confusing and are only further obscured by poor transliteration of Arabic, gaps, or corruption during the copying of manuscripts. Indeed, it often seems that observation stopped with the Arabs and that, once astrology fell into desuetude among in Islamic culture, the system became stuck.

Traditionally in both the Indian and Arabic systems the first Mansion was Al Thurayya (the ‘Many Little Ones’; Indian, Krittika, the ‘General of the Celestial Armies’; Greek, the Pleiades) located in the shoulder of the constellation of Taurus. With the systematisation of Greek astronomy and the establishment of the the Sun’s position at the Vernal Equinox as the First Point of Aries and the start of the Zodiac, the Mansion associated with the star Sheratan, Al Sharatain, became the first Mansion — Botein seems to have missed out. Sheratan (Beta Arietis) is one of the horns of Aries and the name, meaning the "Two Signs", refers to it as a marker for the Zodiac’s beginning along with Mesarthim (Gamma Arietis); the Mansion is also called Alnath, meaning "the one that butts" and, though this name was more common in European usage, it is liable to confusion with another butter, the bright star in upper horn of Taurus, also called Al Nath or El Nath (Beta Tauri, traditionally shared with Auriga). This Mansion, associated with the horns of Aries, is listed as the first by Abenragel (fl. 1000 CE) and Ibn ‘Arabi (1165-1240 CE), and this is the order that passed into European astrology, so that Alnath is mentioned as the first Mansion by Chaucer (1340-1400) and Agrippa (1486-1535). Johannes Hispalensis, writing in the 1140s, does not tie the Mansions to the tropical Zodiac, starting the first Mansion, Horns of Aries, at 16° 01' Aries, and places the previous Mansion, the Fish (Al Batn al Hut), at the end of the list but starting at 3° 09' Aries. However, if the boundaries of the Mansions are tied to a starting point in the tropical Zodiac, which is usually 0° Aries, when adaptations come they tend to be discrete shifts, displacing the sequence through the whole span of a Mansion, 12º 51' 26", or even two, as in the change from Al Thurayya to Al Sharatain. The list which George Yeats copied out from Athanasius Kircher places his equivalent of Al Batn al Hut (the Fish) aligned with 0° Aries, close to Johannes Hispalensis’ arrangement, but at the head list. If the system is taken as purely sidereal, then it cannot be fixed to any particular point and will shift gradually every year; if the marker stars are used, precessional slippage means that the star that is currently closest to 0° Aries is Scheat (Beta Pegasi; which will reach the exact longitude of the Spring Equinox in 2045), one of the markers of Al Fargh al Mukdin, the First Water Spout.

An example of the confusing situation, based on one of the clearer and better known stars, Alpha Tauri (Aldebaran), which gives its name to one of the Mansions, may give some indication. Aldebaran ('the follower' of the Pleiades) is usually identified with the eye of the constellation of Taurus, the Bull, and the name is one of the most distinctive and least liable to corruption since it comes from this star, which was one of the four Royal Stars of ancient Persian astronomy.

- In purely sidereal terms, and therefore in both Zodiacs at the date of coincidence (circa 200 CE), it is located at 14º 35' of Taurus, at about the mid-point of the Zodiac-sign’s 30º range; by 1900 its position in the tropical system had shifted almost 24 degrees to 8º 27' of Gemini.

- Abenragel and Picatrix place the start of the Mansion at 8° 34' 18" Taurus, which is a value based on the position of 0° Aries around the year 1000 CE.

- Agrippa, writing in 1509 (and published in 1531), locates the Mansion, called Aldebram or Aldelamen, and glossed as the eye of the Bull or the head of the Bull, as the fourth Mansion spanning the space between 8º 34' 17" and 21º 25' 43" Taurus. This is justifiable as he is writing about what people used to do, and it appears that he is drawing to a large degree on the Picatrix.

- Abenragel’s works when published in translation in the sixteenth century carry the values which were valid when he wrote, and with the name somehow garbled into Addauennam.

- Francis Barrett used Agrippa’s De Occulta Philosophia almost three centuries later as the basis for The Magus (1801).

Those who do not just follow sources create different problems:

- Joannes Hispalensis, giving a list for 1142 (but published in 1548), does not fix the Mansions to the tropical Zodiac, so he has 'Caput Tauri', the head of the Bull, starting at 11º 43' Taurus and separately 'Oculus Tauri', the eye of the Bull (Al Dabaran), starting at 24º 35'.

- Robert Fludd, writing in 1617, gives no names and only attributes, but places the first Mansion at 27° 53' Aries, while the 27th starts at 2° 25' Aries. It is difficult to tell which of the Mansions corresponds to Al Dabaran, but the third starts at 23° 37' Taurus.

- Athanasius Kircher’s lists, written in the 1650s but with an historical approach, have the eye of the Bull as the fifth Mansion starting at 21° Taurus.

- Coming to the twentieth century, Vivian Robson’s book, The Fixed Stars and Constellations in Astrology, was published in 1923; it was in the Yeatses’ Library (YL 1772) but did not appear until after the bulk of the Automatic Script and the Yeatses’ research. He takes a comparative and historical approach, giving Indian, Arabian and Chinese systems. The list of the Arabian Mansions starts with Al Thurayyah, making Al Dabaran the second Mansion, and takes the stars as markers (so that 0° Aries is not the start), has the Mansion starting at 8° 40' Taurus.

Other writers complicate matters differently, Guido Bonatti for instance adding a separate subcycle of Mansions, but discounting the Mansion in which the New Moon takes place, since the Moon’s effect is obliterated by the Sun. Arcandam (Al-Qalandar, also Alchandreus), apparently a tenth century writer whose astrological works were among the first to enter Europe, adopts a completely different methodology and dispenses with such fractional divisions, locating the Mansions squarely within the signs either in pairs or threes, putting Cocebran in the centre of Taurus (10º-20º), a solution similar to that eventually adopted by the Yeatses.

. . . back to the Yeatses

The Instructors had discouraged Yeats from wider reading in the early stages of the System’s development and had also denied that "Any use [was] made of apparent use of symbolic motion of ![]() opposite to

opposite to ![]() " (sic), asserting that the phasic divisions were "symbolic & arbitrary only" (22 January 1918; YVP 1 275). It was also clear that the Phases assigned to various people bore no relation to the phase of the moon at the time of a person’s birth, as would be the case in an astrological system. The Instructors assigned Phases to people whom the Yeatses knew early on, and in many cases Yeats knew these people’s charts well: his own Moon would be placed astrologically at Phase 18 or 19 (depending on the divisions) rather than 17, George’s at 25 or 26 not 18, while Maud Gonne, instead of being placed in Phase 16, would be born in the non-human Phase 15. In this sense at least, it was evident that the System was not astrological.

" (sic), asserting that the phasic divisions were "symbolic & arbitrary only" (22 January 1918; YVP 1 275). It was also clear that the Phases assigned to various people bore no relation to the phase of the moon at the time of a person’s birth, as would be the case in an astrological system. The Instructors assigned Phases to people whom the Yeatses knew early on, and in many cases Yeats knew these people’s charts well: his own Moon would be placed astrologically at Phase 18 or 19 (depending on the divisions) rather than 17, George’s at 25 or 26 not 18, while Maud Gonne, instead of being placed in Phase 16, would be born in the non-human Phase 15. In this sense at least, it was evident that the System was not astrological.

If it was not the Phase of the Sun and Moon, however, it was always possible that there was something to do with the Moon’s absolute position. Again, from their knowledge of the birthcharts of some of the people involved, it was fairly clear that it would not be any simple alignment, but they may have considered it worth investigating a little. At the very least Yeats would have been interested in another set of symbolism.

From notes and references in the Automatic Script, it is clear that the Yeatses devised an alignment of the Instructors’ Phases with the Zodiac fairly early on for their own use. In many comments, they treat the Phases as having stellar counterparts, such that fixed stars are identified as positioned at certain Phases and planets as transiting or passing through them, exactly as in conventional astrology. None of the background apparatus to this schema appears in the Script itself and evidently the Yeatses were developing the ideas elsewhere before bringing them to the evening sessions. This fixed alignment is linked to the Universal Man, and they had a different method of marrying up the individual’s horoscope and Phase (placing the Ascendant at the centre of the Phase, see Astrology).

Even if there were correspondences between the Phases of the Universal Man and the traditional Mansions, trying to connect the Mansions to their Instructors’ Phases would never have been straightforward, not least because of the difficulty of determining which Mansion started the series and where. In the published versions of the System, Yeats used the precession of the equinoxes for a rather different purpose. In the published versions, they eventually decided on symbolic rather than mathematical allocations with respect to the Great Year (which is linked to the Universal Man), and these allocations are arbitrary, fitting the divisions to whole Zodiac signs, rather than natural, dividing the circle by twenty-eight. A normative pattern of assigning mansions to signs of the Zodiac in twos and threes is seen in some Arab writers, such as Arcandam, and mediaeval manuscripts, but the Yeatses took the arbitrariness to a more extreme degree, allotting a whole sign to the crucial Phases 1, 8, 15 and 22, while allocating the others in triads (see the Cardinal Phases and Triads).

All the same, it would be very strange if the Yeatses had not consulted Joannes Hispalensis, Cornelius Agrippa, or one of the several other resources at some stage. Understandably, however, they did not pursue such researches to any significant extent, since the one thing that all the systems have in common is that they are positional divisions of the Zodiac and as such have very little to do with the Moon’s phasic changes.

Images and Talismans

|

from Francis Barrett, The Magus, or Celestial Intelligencer (1801) |

The Yeatses did develop a set of images, one for each of the Phases, Symbols of the Phases, and to some extent their interest in the Mansions of the Moon may have been as much to do with the symbolism involved rather than direct correspondence. The signs of the Zodiac are very simple images, usually just an animal, whereas the Mansions tend to be associated with slightly more complex images, often of situations or specific individuals, though examples such as the fish and the head of a lion show the influence of the Zodiac.

The nature of these images seems in part to derive from the association of the Mansions with talismanic magic in the Middle Ages and early Renaissance (and still today, according to a website on Renaissance Astrology and Magic). The following Mansions and Images are given by Agrippa (for a comparison of the Images with Bruno’s for the Mansions of the Moon, see Phase Images). See Three Books of Occult Philosophy, Book II, Chapter 46 (link to another web-site for the full text of J. F.’s English translation of 1651). Agrippa tells how the talismans used to be made when the Moon was in a particular Mansion, with appropriate materials and perfumes, apparently distancing himself by claiming simply to record what was done rather than to instruct. The names are often recognisable corruptions of the Arabic ones (similar to but different from those in the translation of Abenragel above), while the Latin names coincide almost entirely with those given by Joannes Hispalensis.

| The Mansions of the Moon according to H. C. Agrippa’s Occult Philosophy, 1533 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| name | (name – Latin) | from | significance | Talisman for | with image of | |

| 1 | Alnath | horns of Aries | 0° Aries | journeys and discord | the destruction of someone | A black man in a garment made of hair, and girdled round, casting a small lance with his right hand |

| 2 | Albothaim Albocham | belly of Aries | 12°51'22" Aries | finding treasure and retaining captives | reconciliation with a prince | A king crowned |

| 3 | Achaomazone Athoraye | rainy ones or Pleiades | 25°42'51" Aries | profits sailors, huntsmen, alchemists | happy fortune and every good thing | A woman well clothed, sitting in a chair, her right hand being lifted up on her head |

| 4 | Aldebram Aldelamen | eye or head of Taurus | 8°34'17" Taurus | destruction and hinderances of buildings, fountains, wells and gold mines, the flight of reptiles and creates discord | revenge, separation, enmity & ill will | A soldier on a horse, holding a serpent in his right hand |

| 5 | Alchataya Albachaya | ( ) | 21°25'40" Taurus | helps safe return from journey, instruction of pupils, confirms buildings, gives health and good will | the favour of kings and officers | The head of a man |

| 6 | Alhanna Alchaya | little star of great light | 4°17'09" Gemini | favours hunting, besieging towns, revenge of princes, destroys harvests and fruits, hinders medicine | to procure love betwixt two | two images embracing one another |

| 7 | Aldimiach Alarzach | arm of Gemini | 17°08'34" Gemini | brings money and friendship, profits lovers, disperses flies, destroys teaching authorities | to obtain every good thing | A man well clothed, holding his hands up to heaven as it were praying and supplicating |

| 8 | Alnaza Anatrachya | misty or cloudy | 0° Cancer | creates, love, friendship, travellers’ fellowship, drives away mice, confirms captivity | victory in war | an eagle having the face of a man |

| 9 | Achaam Alcharph | eye of Leo | 12°51'22" Cancer | hinders harvests and travellers, creates discord between men | to cause infirmities | The image of a man wanting his privy parts, shutting his eyes with his hands |

| 10 | Algeliache Aglebh | neck or forehead of Leo | 25°42'51" Cancer | strengthens buildings, extends love, good will and help against enemies | to facilitate child-bearing | The head of a lion |

| 11 | Azobra Ardaf | Leo’s mane | 8°34'17" Leo | helps journeys and money from commerce, and redeeming captives | fear, reverence and worship | A man riding a lion, holding the ear thereof in his left hand, and in his right, holding forth a bracelet of gold |

| 12 | Alzarpha | tail of Leo | 21°25'40" Leo | prospers harvests and plantations, betters servants, captives and allies, but hinders sailors | the separation of lovers | A dragon fighting with a man |

| 13 | Alhayre | dogs or winged ones of Virgo | 4°17'09" Virgo | favours benevolence, money, voyages, harvests, freedom of captives | the agreement of married couples and for dissolving charms against copulation | images of man in red wax and woman in white wax embracing |

| 14 | Achureth, Arimes, Azimeth, Albumech, Alcheymech | Virgo’s ear of corn | 17°08'34" Virgo | favours marital love, healing of sick, good for journeys by sea but bad for land | divorce and separation of the man from the woman | A dog biting his tail |

| 15 | Agrapha Algarpha | covered or flying covered | 0° Libra | good for extracting treasures, digging pits, helps divorce, discord, destruction of houses and enemies, hinders travel | friendship and goodwill | A man sitting and inditing letters |

| 16 | Azubene Ahubene | horns of Scorpio | 12°51'22" Libra | hinders journeys and marriage, harvests and commerce, but helps redemption of captives | much merchandising | A man sitting on a chair, holding a balance in his hands |

| 17 | Alchil | crown of Scorpio | 25°42'51" Libra | improves bad fortune, helps love to last, strengthens buildings, helps sailors | against thieves and robbers | An ape |

| 18 | Alchas Altoh | heart of Scorpio | 8°34'17" Scorpio | causes discord, sedition, conspiracy against powerful, revenge from enemies, but frees captives and helps buildings | against fevers and pains of the belly | A snake holding his tail above his head |

| 19 | Allatha, Achala, Hycula, Axala | tail of Scorpio | 21°25'40" Scorpio | helps besieging and taking of cities, driving people from positions, destroys sailors and captives | facilitating birth and provoking the menstrues | A woman holding her hands upon her face |

| 20 | Abnahaya | the beam, transom | 4°17'09" Sagittarius | helps taming beasts, strengthens prisons, destroys allies’ wealth, compels a man to come to a certain place | hunting | Sagittary, half a man and half an horse |

| 21 | Abeda Albeldach | the desert | 17°08'34" Sagittarius | favours harvests, money, buildings, travellers, causes divorce | the destruction of somebody | A man with a double countenance, before and behind |

| 22 | Sadabacha, Zodeboluch, Zandeldena | the shepherd | 0° Capricorn | incites the flight of slaves and captives, helping escape, and curing of diseases | the security of [i.e. to catch] runaways | A man with wings on his feet, bearing an helmet on his head |

| 23 | Sabadola Zobrach | swallowing | 12°51'22" Capricorn | causes divorce, freedom of captives, healing of sick | destruction and wasting | A cat having a dog’s head |

| 24 | Sadabath Chadezoath | star of fortune | 25°42'51" Capricorn | helps marital understanding, victory of soldiers, causes disobedience, hindering execution of authority | the multiplying of herds of cattle | A woman giving suck to her son |

| 25 | Sadalabra Sadalachia | the butterfly, unfolding | 8°34'17" Aquarius | helps siege and revenge, divorce, prisons and buildings, speeds messengers, destroys enemies, helps spells against sex or to cause impotence | the preservation of trees and harvests | A man planting |

| 26 | Alpharg Phtagal Mocaden | the first drawing, draining | 21°25'40" Aquarius | helps union, love of men, health of captives, destroys prisons and buildings | love and favour | A woman washing and combing her hairs |

| 27 | Alcharya Ahhalgalmoad | the second drawing, draining | 4°17'09" Pisces | increases harvests, revenues, money, heals illnesses, weakens buildings, prolongs imprisonment, endangers sailors, and helps bringing evils against anyone | to destroy fountains, pits, medicinal waters and baths | A man winged, holding in his hand an empty vessel, and perforated |

| 28 | Albotham Alchalh | the fishes, Pisces | 17°08'34" Pisces | increases harvests and commerce, helps the safety of travellers in dangerous places, causes marital harmony, but strengthens prisons and causes loss of treasures | to gather fishes together | A fish |

[?]uncertain pronunciation but closest

[?]uncertain pronunciation but closest